by Paul L. Heck

November 8, 2020

2024 isn’t far off. We’ve got four years to reset as a nation.

Biden has promised to be president of all.

What do we want the nation to look like at the end of his four years in office?

It’s first worth noting one thing regarding the soon-to-be former president. If the 2020 elections taught us anything, it’s that character matters if you want to rule a nation.

Don’t we all rule the nation? How does one acquire character … and grow in character?

It’s no idle query. Come 2024, when Biden leaves office, the nation may well be as divided as it is now, and we’ll have no one to blame.

The future is unknown, as 2020 has taught us, but we have choices on the menu. Will it be a food fight … or a banquet that satisfies all?

I’ll begin by getting one item off the table: I assume the vast majority understand that growth has to be for all and not only for the few. I leave it to brighter economic minds to explain how that might happen.

Now on to other issues …

First, lots of whites voted for Trump, including college-educated whites. Racism is not just our problem. It’s a global one. But when it comes to the legacy of all being created equal, we claim it as our own. We should therefore set a good example.

How to make it real?

Every group has made great contributions. We wouldn’t be America without Black America. Or Hispanic America. Or (fill-in-the-blank) America.

Can we gaze at each group with wonder and admiration for the gifts it brings to the nation?

The key lies in the gaze. How do you gaze at your fellow citizen? Spend some time calibrating your gaze. I will too.

Second, lots of non-whites voted for Trump, including a good number of Hispanics.

Yes, anxieties over race aren’t going away.

Why is the black body not seen as being sacred as the white body is? What makes a body sacred? What color is the nation’s body? Why do we see it as a white body? All races drape their bodies in the flag.

But it’s not only race. Our demographics are changing and so are our fault lines.

Immigrants are good for the economy. All research shows that. But who are they?

They want a fairer economy, and they have more conservative views on marriage and family. They come from societies more traditional than ours. Shifting demographics won’t always favor liberal views.

And let’s be honest: People don’t change their minds on hot-button issues. It’s not a question of law. (If it doesn’t protect all, it’s not law.) It’s a question of worldview. Can we get to a point where none—conservative or liberal—feel compelled to celebrate a worldview that’s not theirs?

That’s key. We live in a nation with two opposing worldviews, each with a logic of its own. Your values win, mine lose … or vice versa.

Many breathed a sigh of relief when the election results were called.

But there are many who feel less safe. The Biden election may embolden the cancel culture. Many won’t say what they believe for fear of losing their job or getting cancelled.

This brings us to Christianity. All religion in the country is of concern here, but Christianity has long been the majority religion. It now evokes deeply contrary feelings.

It wasn’t long ago that Christianity was a vital part of the nation’s mission—the struggle against communism. Now, depending on where you live, you may find more than a few people who want all traces of it erased from public view. Whose beliefs are to going to get a public viewing in the years ahead?

Broadly speaking, there are two types of Christianity in the nation: liberal and conservative. Both take their cue from politics.

(There’s actually a third: Let’s call it traditional. It doesn’t take its cue from politics. To speak of my own Catholic community, both liberal and conservative Catholics read the faith through a political lens. It’s not been good for church unity. Traditional Catholics are public with the church stuff they do—praying, serving, educating—but don’t see the politics of the day as reflecting on the faith.)

Liberal Christianity will accept the Biden-Harris mandate as expression of the Christian message.

As for conservative Christians, they had it good under the Trump-Pence administration. Are they destined to become the nation’s non-conformists under Biden-Harris?

They won’t take their new role lying down. They’ll lobby for their interests, as all groups do, but they face a crisis about their relation to the nation.

Under Biden-Harris, they won’t see the nation as their nation. They’ll feel like strangers.

Don’t they deserve it? After all, haven’t they long defined the nation in their image, leaving others out of the picture?

There’s lots of simplistic narratives out there, including narratives about Christians, even conservative ones.

If you’re not Christian, get to know one. Ask them what they believe. If you are, get to know others. Ask them what they believe.

I’d like to think that facts can hold us together as a nation—basic data on what works and what doesn’t work when it comes to our common life … and basic data that upends fake news.

But we don’t share the same moral realities, and that makes it difficult for us to trust each other when it comes to facts.

Are we willing to admit that? If not, the problem won’t go away. Admission is the first step.

The place of religion in America is at the heart of this divisive moment in the nation’s history.

The overlapping consensus is long gone—at least as it was formulated over the last century.

It’s not about getting to agreement. That won’t happen, and so it can’t be the goal. And the nation has always known clash. It’ll still be there in 2024.

I say this: Religion in America is a question for the rising generations to decide. They don’t view it as the nation viewed it during the Cold War.

This is the point: Religion will remain indelible part of the nation’s fabric, but it won’t look like what the last century accustomed us to think religion should look like.

The rising generations, polls suggest, lean a little more pro-life and a lot more pro-climate. They aren’t bothered about different ways of forming a family. And they’re stridently ambiguous on religion.

On the one hand, they’re less religious when it comes to church membership.

On the other, they’re very religious in terms of commitments. They have a transcendent mindset.

They’re not interested in creeds and institutions, but they are fervent about the big questions, which are never far from religious concepts. Think sacrifice, for example.

This odd combination—indifferent to creeds and institutions, fervent about humanity’s ultimate realities and final goods—is key to understanding how religion in America is going to look in the years ahead.

And let’s not forget that beliefs are key to what makes us Americans. It’s because of our beliefs, secular or religious, that we’re protected from the tyranny of the state.

To put it differently, the first amendment is what makes us all religious in some fashion. If we didn’t have our constitutionally protected beliefs, we’d be susceptible to tyranny.

But, of course, clash over religion in America may just increase the next four years. We don’t know how to talk about religion. We’re a theologically challenged nation … one of many but one all the same.

One last point: I’m a little concerned that our national impulse to save the world is going to kick in again the coming years. (I’ve been hearing sentiments to that effect in DC cafes the last couple days.)

Trump was pulling us back from excessive internationalism. He might not have done so with a vision. And he unnecessarily alienated our allies.

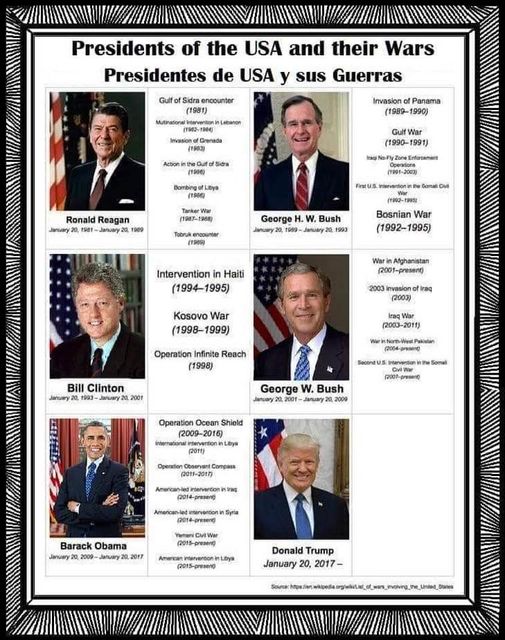

But look at the last several decades.

War-making has become part of our national character. To cite one instance: The two Bushes—father and son—got us into disastrous wars, harming us as a people—our economy and our character. (And the war-making came home in the form of militias and militarized police forces.)

But the issue lies deeper than war-making. It’s about our savior complex, which is now a decidedly secular project. When it kicks in, war-making is sure to follow sooner or later.

We need to discuss what makes us strong as a nation. Is it our military might?

Or our ability to innovate—our openness to endless possibility?

Where do we want to be in four years? The end of Trumpism isn’t going to make getting there any easier.